CDC(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

最近安倍総理大臣もこの言葉を覚えた模様で「日本版CDC」をというような使い方がなされています。業界の人にとっては、ガイドラインを出しているのでその周辺でお目にかかることが多いのではないかと思います。私は、1995年公開の映画「アウトブレイク」で初めて耳にしました。1999年に留学したFDAとは、同じHHSの下部組織、つまりFDAとCDCは組織図上は横並びでした。CDCはどういった仕事をしているのでしょうか?業務は多岐にわたります。CDCの仕事を身近に感じたのは、1999年留学した年に、テレビで「鳥の死骸から西ナイルウイルスが検出された」という発表でした。米国には鳥の死骸のウイルス検査をしている行政機関があることに驚きました。その後ニューヨークでは夜間にヘリコプターで住宅街に殺虫剤をまくというプロジェクトが放送されていました。夜間に殺虫剤をまくので窓を閉めて寝るようにという放送がされていました。テレビの放送によると、「人体には無害な殺虫剤をまくが、念のため窓を閉めておくように」という事でした。

次に私が目にしたのは、FDAのCBERと共同してワクチンの副反応を集めて集計している業務です。パピローマウイルスワクチン、いわゆる「子宮頸がんワクチン」を知り合いたちと集計したのを覚えています。当時日本では上市前でしたが、すでに上市されていた米国のデータではStill病のような副反応が報告されているという内容でした。

サーベイランスのアルゴリズム

そして今回の新型コロナウイルス肺炎の騒ぎで、伝染病のサーベイランスと結果次第では早めの対応を日本でもできるようにという事で、「日本版CDC」をという議論が出てきているのだろうと思います。ただ、良く判らないのがその機能を担う機関が日本に全くないのかというとそういう訳でもないように思います。それは、さておき感染症のサーベイランスはどんな風にデータを評価しているのか少し調べてみました。Getting started with outbreak detection (アウトブレイクを検出することから始めよう)という論文によるとCDC algorithmという手法があります。新たに発症した症例数を週ごとに集計して、過去の発症例数と比較して変動の範囲を超えて感染者が増加した場合に、そのシグナルを検出する手法です。どんなふうになるのか、論理的な事や数式が出てきて良く判らなくなるよりは、実際のCOVID-19の日本のデータ(3月10日までの集計)を流し込んでどういったアウトプットが得られるのか、ながめてみることにしました。

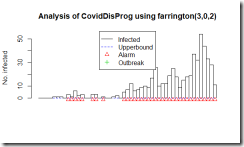

とりあえず結果です

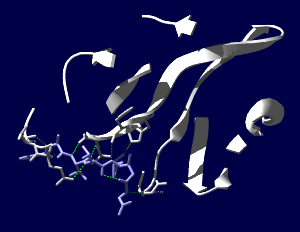

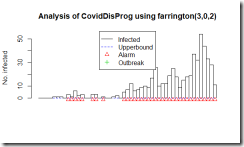

図はFarringtonアルゴリズムの出力です。四角い柱で1日ごとの度数が表示されています。右端のピークが3月6日。初めのアラートが1月28日(3例報告の日)。

実は、CDCが感染の流行をモニターしているアルゴリズムは週ごとのデータしか解析しないということで、今回のような短期のデータを日ごとで集計しようとするとエラーになりました。そこで教科書にCDCのアルゴリズムと列挙されていましたもう一つのアルゴリズム Farringtonのアルゴリズムで集計してみました。とりあえず、過去50日分の報告件数から、変動の範囲内なのか流行の兆しなのかを計算しているようです。この手法は、日ごろから散発的に報告があるような疾患で、急に増えて流行の兆しではないかというのを早期に発見する目的で使用するのに適している様で、COVID-19の様に全く新しい疾患に対しては、この手法は向いていないように思いました。残念。

A statistical algorithm for the early detection of outbreaks of infectious disease, Farrington, C.P.,Andrews, N.J, Beale A.D. and Catchpole, M.A. (1996), J. R. Statist. Soc. A, 159, 547-563.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2983331?seq=1

library(“surveillance”)

library(readxl)

X0020_STS <- read_excel(“COVID_STS.xlsx”)

CovidDisProg <- create.disProg(week = X0020_STS$week,

observed = X0020_STS$observed,

state = X0020_STS$state,

start = c(2018, 1),

freq=365,

epochAsDate=TRUE)

#Do surveillance for the last 50 days.

n <- length(CovidDisProg$observed)

#Set control parameters.

control <- list(b=2,w=3,range=(n-50):n,reweight=TRUE, verbose=FALSE,alpha=0.01)

res <- algo.farrington(CovidDisProg,control=control)

#Plot the result.

plot(res,disease=”COVID-19″,method=”Farrington”)

# sts.cdc <- algo.cdc(CovidDisProg, control = control)

# <<<error>>> algo.cdc only works for weekly data.

# plot(sts.cdc, legend.opts=NULL)

使用した集計済ファイル

https://gis.jag-japan.com/covid19jp/?fbclid=IwAR3FWAcLkQvXDTUUMtNwm7qRFhplIxSREML5m-rrPXWzfz7IxVANOBdSeSY