WAVLINK AC1200という、安価な無線ルーターを使用しています。

少し電力消費が多そう(熱くなる)ので経済的でないかもしれませんが、かなり昔ですが安かったのでポチッとしました。

これを中継機として使用するにあたって、説明書がなくて困りました。ネットで調べたリンクを貼っておきます。

とりあえず、ログインするには、こいつのwifi電波に接続した上で 192.168.10.1 へ接続し、パスワードadmin (当然私はもう変更しています)で設定画面に入れます。

backup

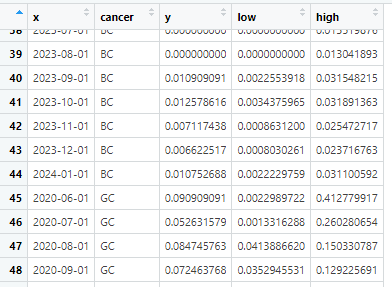

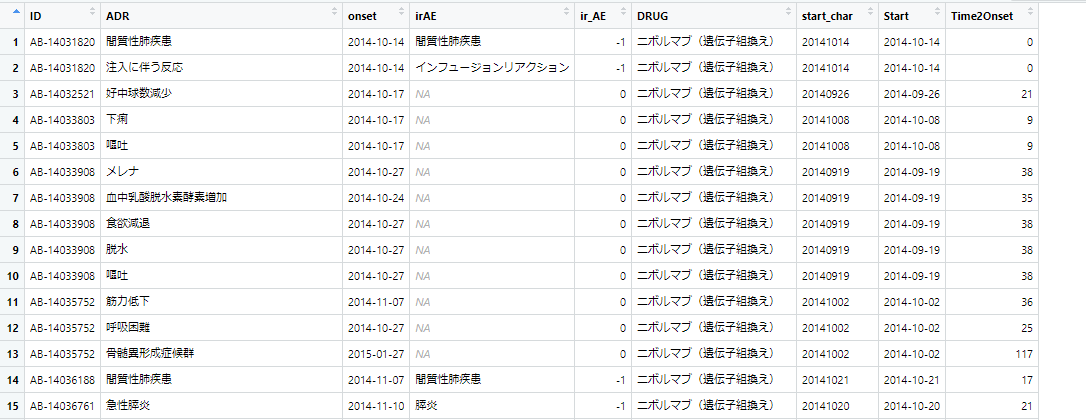

こんな感じのデータがありました

xは時期 as.Date(“2024-03-08”)とかの値が入っているベクター

cancer はc(“GC”, “BC”) がん種の値が入ったベクター

y は表示したい値(平均値とか頻度とか)

low/hight はエラーバーの上限・下限(95%信頼区間とか)

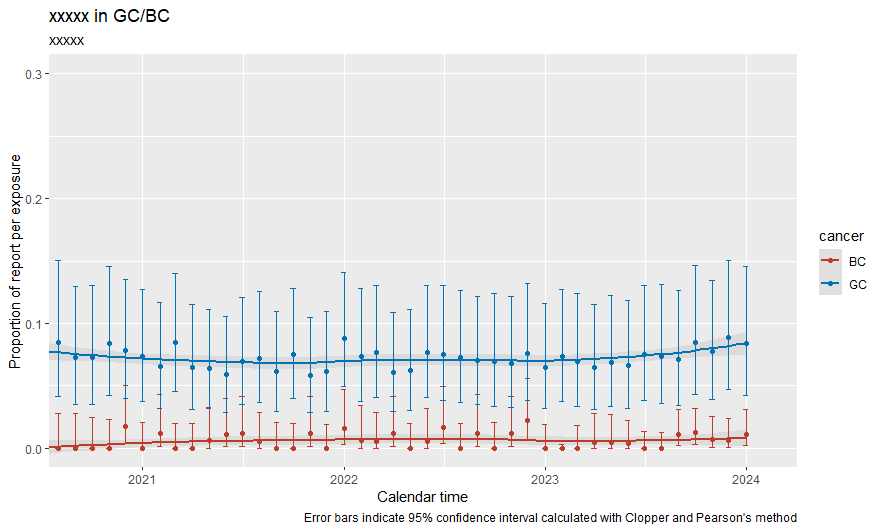

データフレームをがん種別に作成した後に、それらを一つのグラフで表示したくなった

library(ggplot2)

library(ggsci)

library(scales)

BC_data_frame <- data.frame(x, cancer, y, low, high) # BCとGCでそれぞれのベクターには

GC_data_frame <- data.frame(x, cancer, y, low, high) # 異なる値が入っている

combined_data_frame <- rbind(BC_data_frame, GC_data_frame)

g5 <- ggplot(combined_data_frame, aes(x, y, color = cancer)) +

geom_smooth(aes(ymin = low, ymax = high), alpha = 0.2) +

scale_color_nejm() +

geom_point() +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin = low, ymax = high), width = 10) +

scale_x_date(limits = c(as.Date("2020-05-15"), as.Date("2024-01-31")), oob = oob_keep) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 0.2), oob = oob_keep)

plot(g5)

ど

rbindで結合して、そのままプロットしたら2系列が分かれて表示された

全体はこんな感じ

setwd("C:/Users/****")

library(ggplot2)

library(ggsci)

library(scales)

x <- seq(as.Date("2020-06-01"), as.Date("2024-01-01"), by = "month")

k1 <- binom.test(1, 11); y <- c(k1$estimate); low <- c(k1$conf.int[1]); high <- c(k1$conf.int[2])

k2 <- binom.test(1, 19); y <- c(y, k2$estimate); low <- c(low, k2$conf.int[1]); high <- c(high, k2$conf.int[2])

# ... データ個所は中略

k43 <- binom.test(12, 135); y <- c(y, k43$estimate); low <- c(low, k43$conf.int[1]); high <- c(high, k43$conf.int[2])

k44 <- binom.test(11, 131); y <- c(y, k44$estimate); low <- c(low, k44$conf.int[1]); high <- c(high, k44$conf.int[2])

cancer <- rep("GC", 44)

GC_data_frame <- data.frame(x, cancer, y, low, high)

k1 <- binom.test(0, 12); y <- c(k1$estimate); low <- c(k1$conf.int[1]); high <- c(k1$conf.int[2])

k2 <- binom.test(0, 118); y <- c(y, k2$estimate); low <- c(low, k2$conf.int[1]); high <- c(high, k2$conf.int[2])

# ... データ個所は中略

k43 <- binom.test(2, 302); y <- c(y, k43$estimate); low <- c(low, k43$conf.int[1]); high <- c(high, k43$conf.int[2])

k44 <- binom.test(3, 279); y <- c(y, k44$estimate); low <- c(low, k44$conf.int[1]); high <- c(high, k44$conf.int[2])

cancer <- rep("BC", 44)

BC_data_frame <- data.frame(x, cancer, y, low, high)

combined_data_frame <- rbind(BC_data_frame, GC_data_frame)

g5 <- ggplot(combined_data_frame, aes(x, y, color = cancer)) +

geom_smooth(aes(ymin = low, ymax = high), alpha = 0.2) +

labs (title = "xxxxx in GC/BC") +

labs(subtitle = "xxxxx") +

labs( x = "Calendar time",

y = "Proportion of report per exposure",

caption = "Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval calculated with Clopper and Pearson's method" ) +

scale_color_nejm() +

geom_point() +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin = low, ymax = high), width = 10) +

scale_x_date(limits = c(as.Date("2020-09-15"), as.Date("2024-02-01")), oob = oob_keep) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 0.3), oob = oob_keep)

plot(g5)

R でdata frameに対してsql スクリプトを実行できるパッケージのsqldfで、存在しているはずのデータフレームを指定しても’no such table’というエラーが返ってきました

関連するパッケージを最新バージョンへアップデートしたり、Rを再起動したりしたのですが効果はありませんでした。どうやらデータフレーム名に.(ドット)があるとダメなようです。

以下の試行例では、df_LineListではエラーが出ませんがdf.LineListではエラーになってしまいます

> df.LineList <- df_LineList # データフレームの内容は同じ

> df.test <- sqldf('SELECT * FROM df_LineList') # エラーなし

> df.test <- sqldf('SELECT * FROM df.LineList') # こちらではエラーが出る

エラー: no such table: df.LineList

> class(df.LineList)

[1] "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame"

> class(df_LineList)

[1] "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame"

>

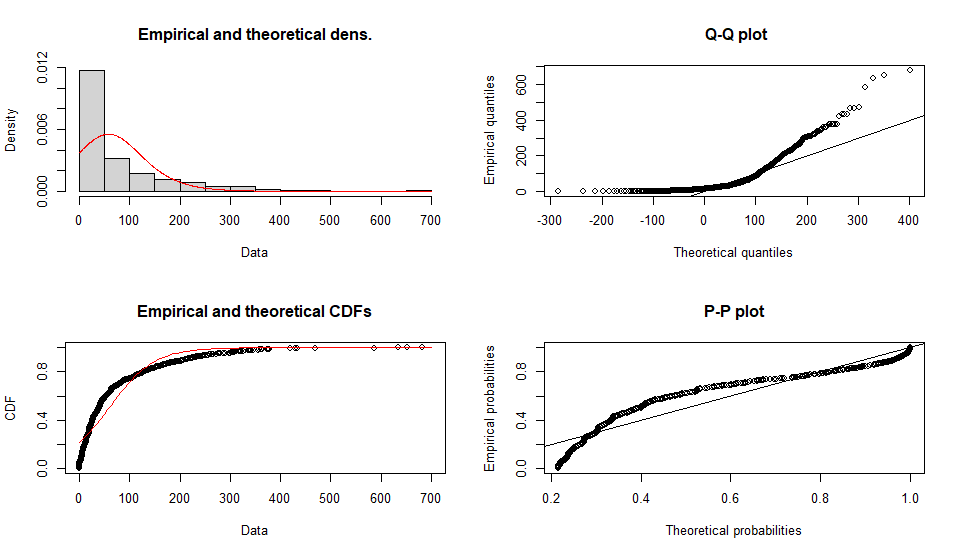

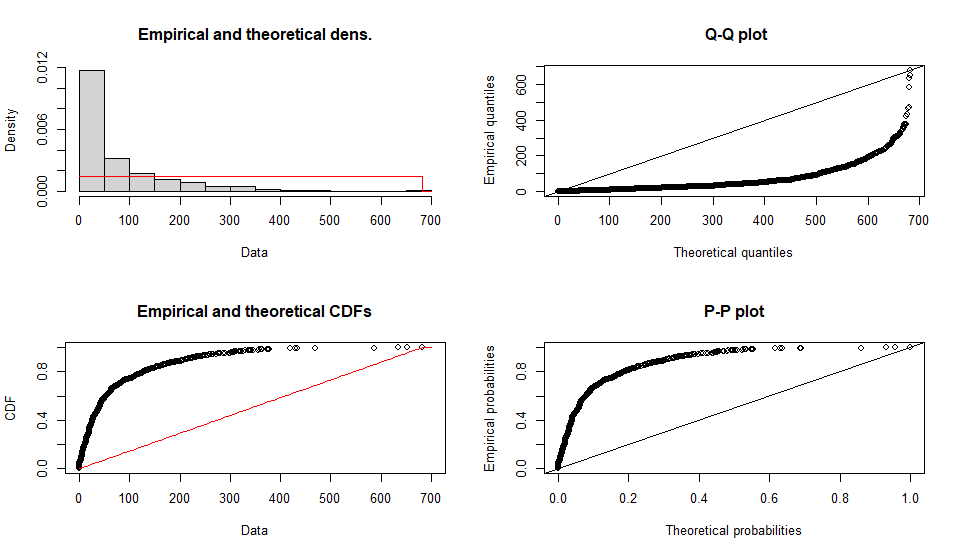

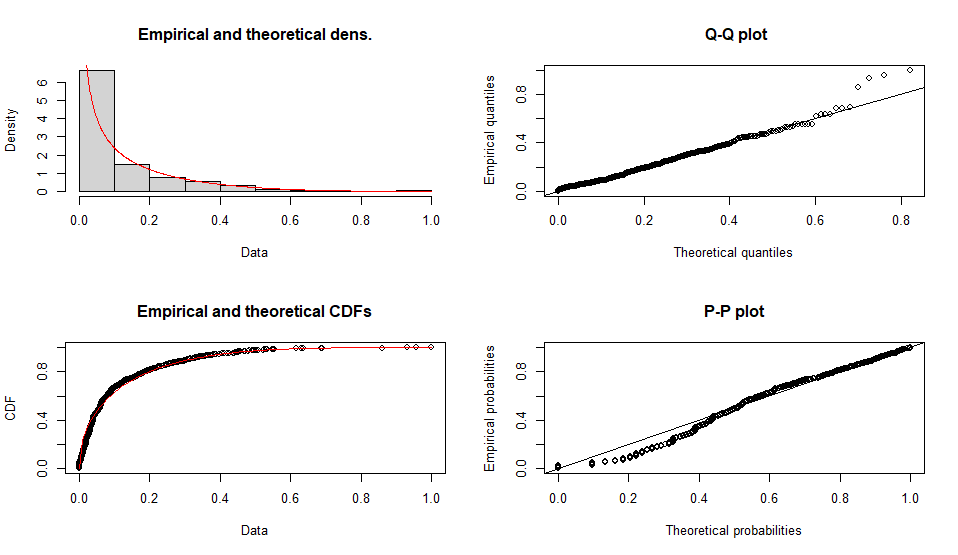

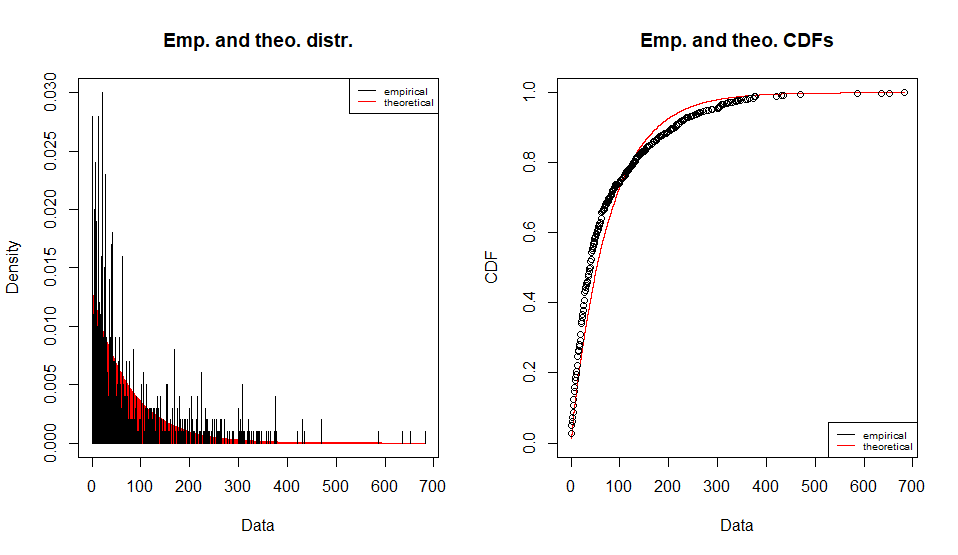

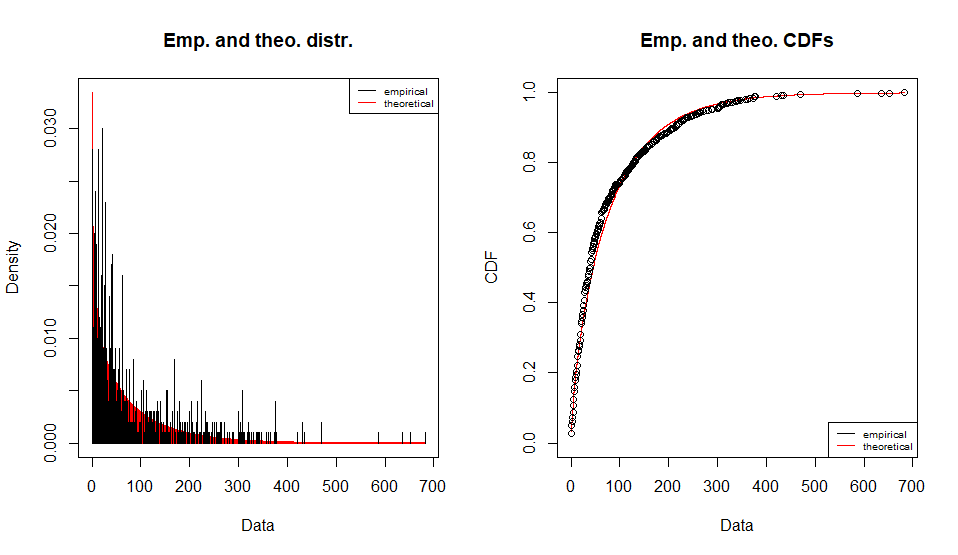

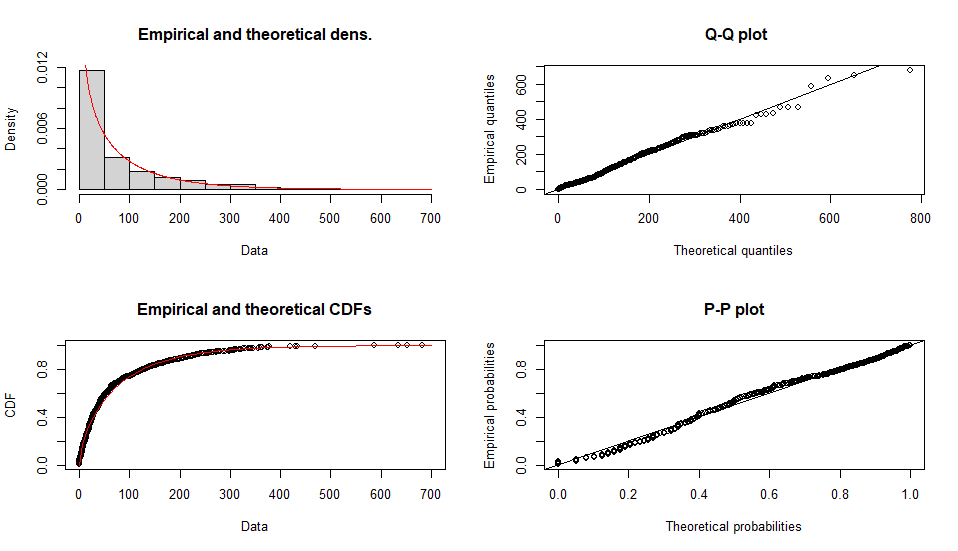

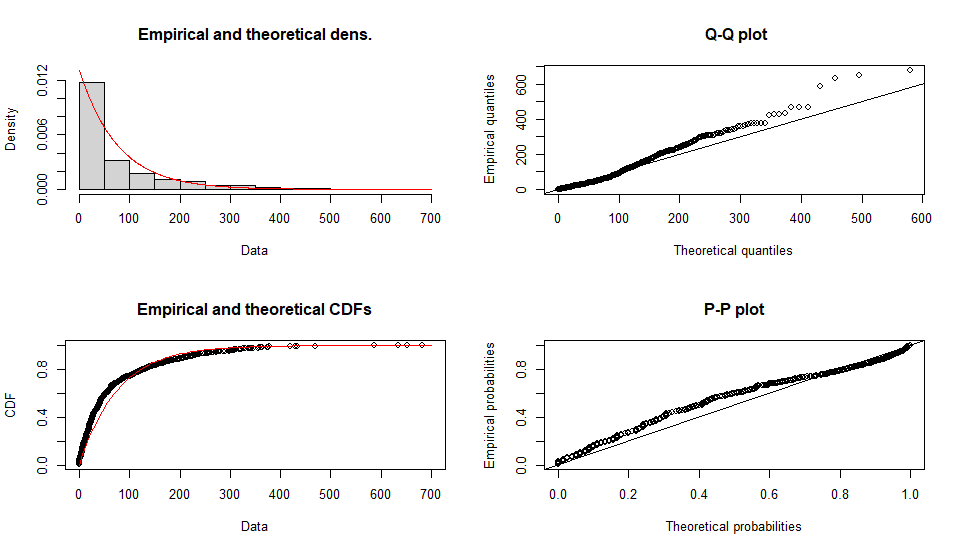

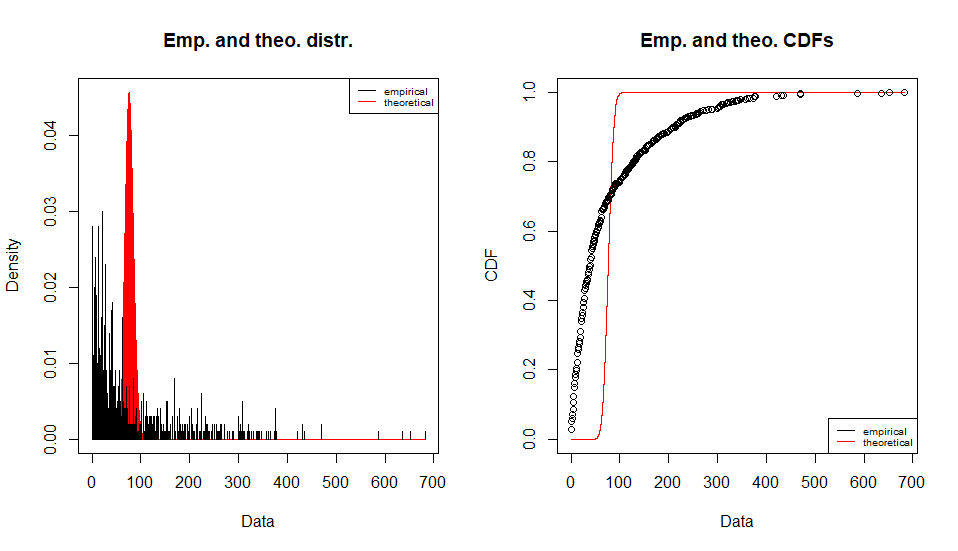

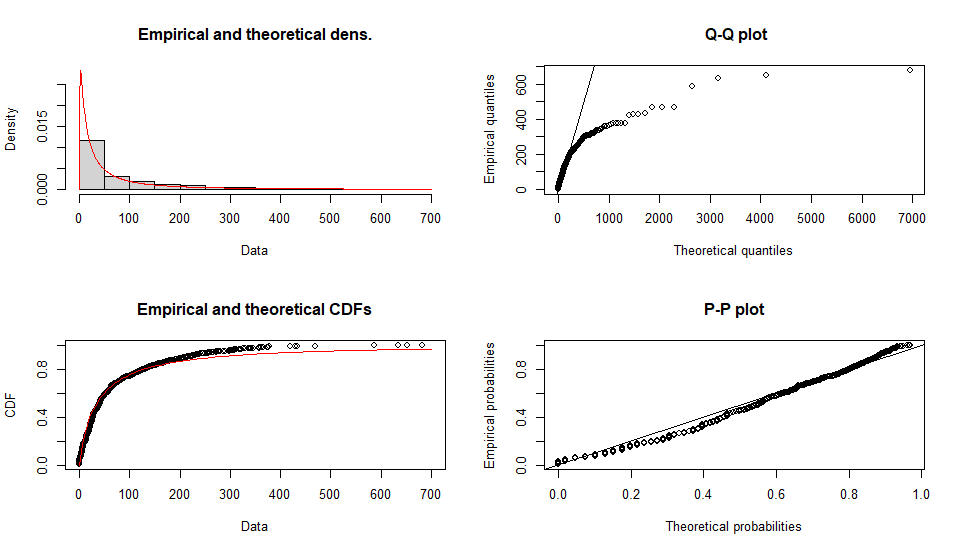

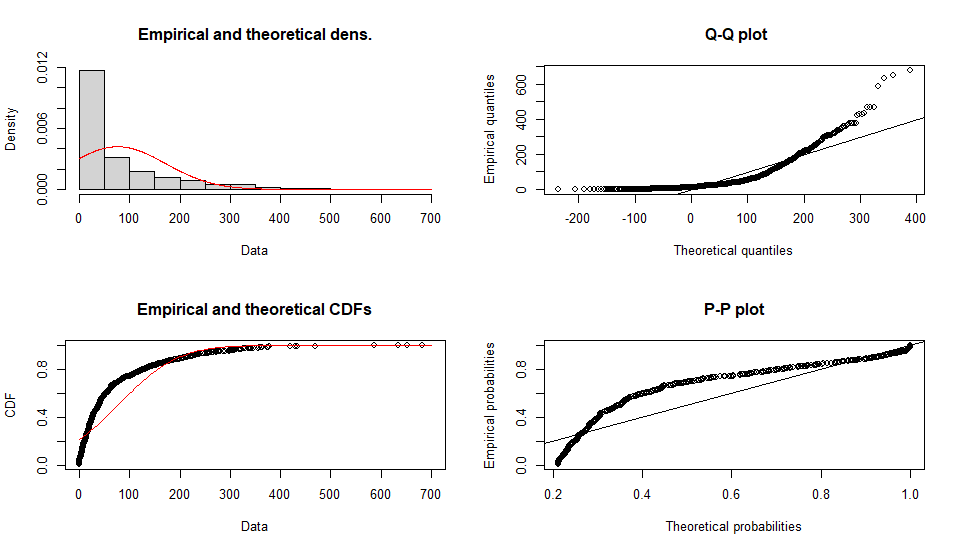

手持ちの単変量の分布を確率密度関数に当てはめて母数を推定する(よくわからない)

使うデータは他のページで作成したdf.testDATA

library(fitdistrplus) # 分布のテスト x <- df.testDATA$Time2Onset y <- max(df.testDATA$Time2Onset) min(df.testDATA$Time2Onset) ################ distribution test ################ normmlefit <- fitdist(x, "norm", "mle"); fit <- normmlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) lnormmlefit <- fitdist(x + 0.1, "lnorm", "mle"); fit <- lnormmlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) poismlefit <- fitdist(x, "pois", "mle"); fit <- poismlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) expmlefit <- fitdist(x, "exp", "mle"); fit <- expmlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) gammammefit <- fitdist(x, "gamma", "mme"); fit <- gammamlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) nbinommlefit <- fitdist(x, "nbinom", "mle"); fit <- nbinommlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) geommlefit <- fitdist(x, "geom", "mle"); fit <- geommlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) betammefit <- fitdist(x/y, "beta", "mme"); fit <- betamlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) unifmlefit <- fitdist(x, "unif", "mle"); fit <- unifmlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit) logismlefit <- fitdist(x, "logis", "mle"); fit <- logismlefit; gofstat(fit); plot(fit)

よくフィットしてそうなのはbetaかgammaの様です

Fitting of the distribution ' logis ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

location 58.31789 2.418478

scale 45.17608 1.249104

Loglikelihood: -5863.559 AIC: 11731.12 BIC: 11740.93

Correlation matrix:

location scale

location 1.0000000 0.1570439

scale 0.1570439 1.0000000

Fitting of the distribution ' unif ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

min 0 NA

max 682 NA

Loglikelihood: -6525.03 AIC: 13054.06 BIC: 13063.87

Correlation matrix:

[1] NA

Fitting of the distribution ' beta ' by matching moments

Parameters :

estimate

shape1 0.4604008

shape2 3.6574364

Loglikelihood: NaN AIC: NaN BIC: NaN

Fitting of the distribution ' geom ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

prob 0.01294465 0.0004042749

Loglikelihood: -5340.572 AIC: 10683.14 BIC: 10688.05

Fitting of the distribution ' nbinom ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

size 0.7293184 0.02936535

mu 76.2394754 2.83607459

Loglikelihood: -5307.489 AIC: 10618.98 BIC: 10628.79

Correlation matrix:

size mu

size 1.0000000000 0.0001760878

mu 0.0001760878 1.0000000000

Fitting of the distribution ' gamma ' by matching moments

Parameters :

estimate

shape 0.644237078

rate 0.008448789

Loglikelihood: Inf AIC: -Inf BIC: -Inf

Fitting of the distribution ' exp ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

rate 0.01311441 0.0004122862

Loglikelihood: -5334.044 AIC: 10670.09 BIC: 10675

Fitting of the distribution ' pois ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

lambda 76.252 0.2761377

Loglikelihood: -48448.44 AIC: 96898.87 BIC: 96903.78

Fitting of the distribution ' lnorm ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

meanlog 3.477753 0.05160282

sdlog 1.631824 0.03648864

Loglikelihood: -5386.39 AIC: 10776.78 BIC: 10786.6

Correlation matrix:

meanlog sdlog

meanlog 1 0

sdlog 0 1

Fitting of the distribution ' norm ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters :

estimate Std. Error

mean 76.25200 3.004195

sd 95.00104 2.124288

Loglikelihood: -5972.826 AIC: 11949.65 BIC: 11959.47

Correlation matrix:

mean sd

mean 1 0

sd 0 1

以前作成したdata frame (df.LineList)のうち、【IFirAE】の値が”IRAE”の行のみを抽出したいという場面の基本的なコード

#irAE症例のみの分布 df.irAE <- df.LineList[df.LineList$IFirAE == "IRAE",]

抽出されたデータフレームは df.irAEというdata frameへ代入されます

df.LineList 数万行のデータで、これを使って集計したい。スクリプトを作成中はトライ&エラーのところがあって、ちょっとスクリプトを書いては試しを繰り返す。その、試しのスクリプトが機能するかを実行するたびに待ち時間が大きい。そこで、一部だけテスト用に抜き出したい、という場面です。

抜き出したdata frame をdf.testDATA へ代入します

#テスト用にはじめ100行のみのデータ df.testDATA <- df.LineList[1:100,]

下図のようなdata frame (df.LineList)があります。【ir_AE】というカラムは、 -1 の場合irAE、0の場合非irAEという情報です。

このir_AEカラムを見ながらirAEかどうかの情報を”IRAE”か”nonIRAE”かという文字列を持つカラム【IFirAE】へ書き込みたいという場合のスクリプト。dplyrパッケージのmutate if_else を使います。

library(dplyr) df.LineList <- mutate(df.LineList, IFirAE = if_else(ir_AE == -1, true = "IRAE", false = "nonIRAE"))

実行すると次のようになります。(右端のIFirAE列が追加されている)

一般化したら次のようになります。(マニュアル)

if_else(condition, true, false, missing = NULL, ..., ptype = NULL, size = NULL)

論理ベクトル

条件の TRUE および FALSE 値に使用するベクトル。 true と false の両方が条件のサイズにリサイクルされます。 true、false、および missing (使用されている場合) は、共通の型にキャストされます。

NULL でない場合は、条件の NA 値の値として使用されます。 true と false と同じサイズと型の規則に従います。

これらのドットは将来の拡張用であり、空にする必要があります。

必要な出力タイプを宣言するオプションのプロトタイプ。 指定した場合、これは true、false、および missing の共通タイプをオーバーライドします。

希望の出力サイズを宣言するオプションのサイズ。 指定した場合、これは条件のサイズをオーバーライドします。

条件と同じサイズ、および true、false、および missing の共通型と同じ型を持つベクトル。

条件が TRUE の場合は true の一致値、FALSE の場合は false の一致値、NA の場合は欠落値の一致値 (指定されている場合)、それ以外の場合は欠落値が使用されます。

SQLならチョイとできるデータの扱いもRだと不慣れで調べながらになるのがもどかしい。もちろんSQLとRを行ったり来たりすればいいのでしょうが、チョイと手間がかかるのと、Rのデータをデータベースへ読み込ませ、それをSQLで加工して、データベースからデータを吐き出して、Rへ読み込ませるというのは、ゴミが入る危険性をはらんでいるのでできれば避けたい作業なのです。

library(sqldf)

df_LineList <- df.LineList

df.new <- sqldf('SELECT *, case

when ir_AE == -1 then "IRAE"

when ir_AE == 0 then "nonIRAE"

else ""

end as IFirAE FROM df_LineList')

(でも、Rのsqldfでやろうとすると、case文の文法が私の馴染んでいるやつと結構違う!

Rで集計しようとcsvのファイルを読み込ませようとしたところマルチバイト文字の読み込みのエラーになりました。’invalid multibyte string at…’の個所。

> JADERdata <- read.csv("0020 PhViDdata.csv", head=T)

Error in type.convert.default(data[[i]], as.is = as.is[i], dec = dec, :

invalid multibyte string at '<8a><e9><90>}'こ

明示的に文字コードを教えてあげると良いと思い 、確かUTF-8だったはずとやったらはずれで

> JADERdata <- read.csv("0020 PhViDdata.csv", fileEncoding="utf-8", head=T) Warning messages: 1: In read.table(file = file, header = header, sep = sep, quote = quote, : invalid input found on input connection '0020 PhViDdata.csv' 2: In read.table(file = file, header = header, sep = sep, quote = quote, : incomplete final line found by readTableHeader on '0020 PhViDdata.csv'

SJIS(シフトJIS)で読み込めました

> JADERdata <- read.csv("0020 PhViDdata.csv", fileEncoding="sjis", head=T) >

調べたらぶぶ漬けは祇園の言葉で京都全域で使う表現ではないとのこと。

上方落語で、ぶぶ漬けを食って帰ろうとする大阪人と、ぶぶ漬け出さずに返そうとする京都人の駆け引きが出てくるお話で有名になった「ぶぶ漬け」の知名度を利用した商売かもしれない。

今回、私史上最高クラスのホテルに宿泊できました。

ボードゲームをする場所の様です。この近くを通ると、時々二人組で(刺しで)ゲームをしている人たちがいらっしゃいました。

大浴場から宿泊棟へもどる途中の共用スペース。卓球台が置いてありました。ひょっとしてこれがいわゆる温泉卓球?

ホテル、いや、ポテルの入り口付近

右側が大浴場。日中は宿泊客以外の方々も銭湯のように使用することができるようでした。左側は酒類など販売している売店。以下、周辺の様子の写真。

ビール他のアルコールやおつまみ類も無料で楽しむことができます。(セブンのチキンはセブンイレブンで購入してきましたが、それ以外はホテルで提供された無料アルコール・おつまみ)

月の石・ドライフルーツ・オレンジジュース

朝食の炊き込みご飯、各種おかず

焼きおにぎりのお茶漬け、温野菜・漬物・黒豆納豆・豆腐梅肉

和菓子・杏仁ヨーグルト

おまけの学会弁当

きっと、今回の出張では太ったな

連絡がありました、AIで歌声の音声を生成する「CeVIO Pro (仮)」(VoiSona正式リリース前のベータ版)0.5.1 は2024年2月13日に配布を終了するとのことです。終了までの配布先は

とのこと