What is Glucose Transporter 1 Deficiency?

What is glucose transporter deficiency?

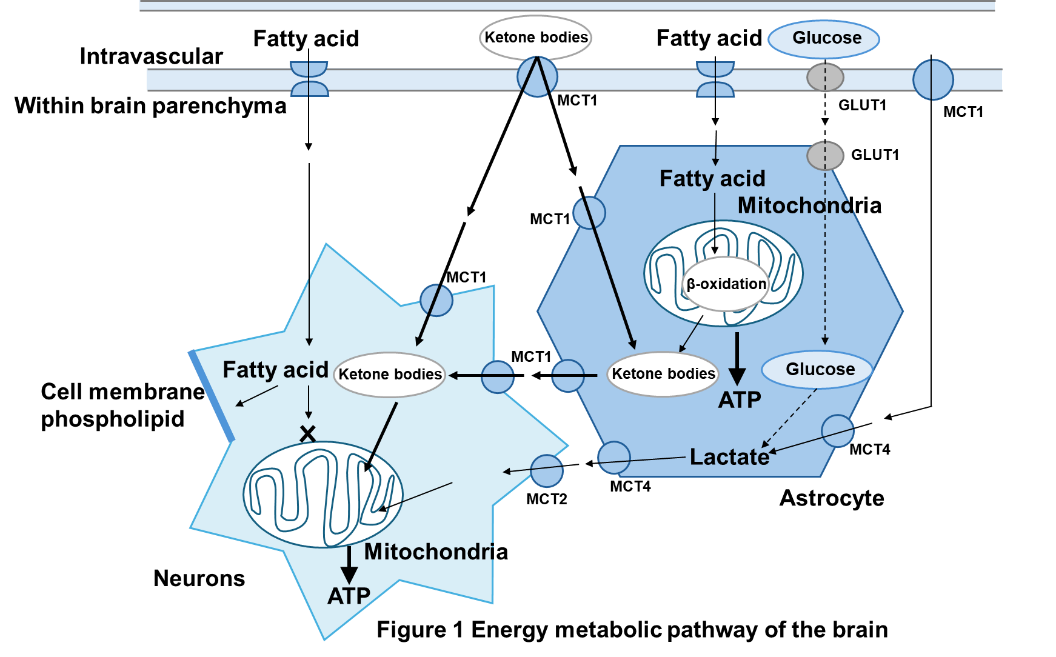

Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) deficiency occurs when glucose, the brain's energy source, is not taken up by the brain (Figure 1). Most patients have a newly developed genetic structural change (mutation) in one of the SLC2A1 genes inherited from both parents. There are also quite a few family cases reported. Mutations in the SLC2A1 gene cause a deficiency in glucose transporter 1, which exists in the endothelium of brain capillaries and transports glucose in the blood to the brain. The brain can normally only use glucose as an energy source. The glucose demand of the brain in children is known to be 3 to 4 times that of adults. If the supply of glucose to the developing brain is insufficient, it will have a significant impact on brain function and development. A patient with a mutation that only retains 50% of the function of the glucose transporter 1 protein is a typical case (more severe type) of glucose transporter 1 deficiency. If the mutation is preserved in about 50 to 75 percent of cases, the symptoms will be milder, but if it is preserved in more than 75 percent of cases, there may be mild cases where only minor symptoms are observed.

Initial symptoms appear in infancy, and include abnormal eye movements, seizures, and holding one's breath (apnea), which may or may not appear during infancy. As the disease progresses, various symptoms appear, such as developmental delays, spastic paralysis, which causes tension when moving the hands and feet, ataxia, which causes dizziness, slurred speech, and clumsiness, and dystonia, which cause muscles to tense up when trying to move the body, making it difficult to move as desired. 80 to 90% of patients have epileptic seizures, and many of these occur in infancy. In addition to epileptic seizures, symptoms such as drowsiness, changes in consciousness, ataxia, motor paralysis, which causes the hands and feet to be unable to move fully, various movement disorders such as dyskinesia, which causes the limbs to move involuntarily, headaches, and vomiting may suddenly appear. These symptoms are characterized by worsening when the patient is hungry (especially in the early morning), exercising, fatigue, lack of sleep, and elevated body temperature, and improving with meals, rest, and sleep.

Epilepsy does not become severe and may improve or even disappear during adolescence. On the other hand, movement disorders such as paroxysmal dyskinesia, spastic paralysis, and ataxia, as well as other paroxysmal symptoms, may appear after adolescence or worsen if they have been present since childhood. Although there are no life-threatening complications, and the disease does not drastically shorten lifespan, early diagnosis and treatment are essential to address the impact on brain function and development due to insufficient glucose supply during critical growth periods.

How is Glucose Transporter 1 Deficiency diagnosed?

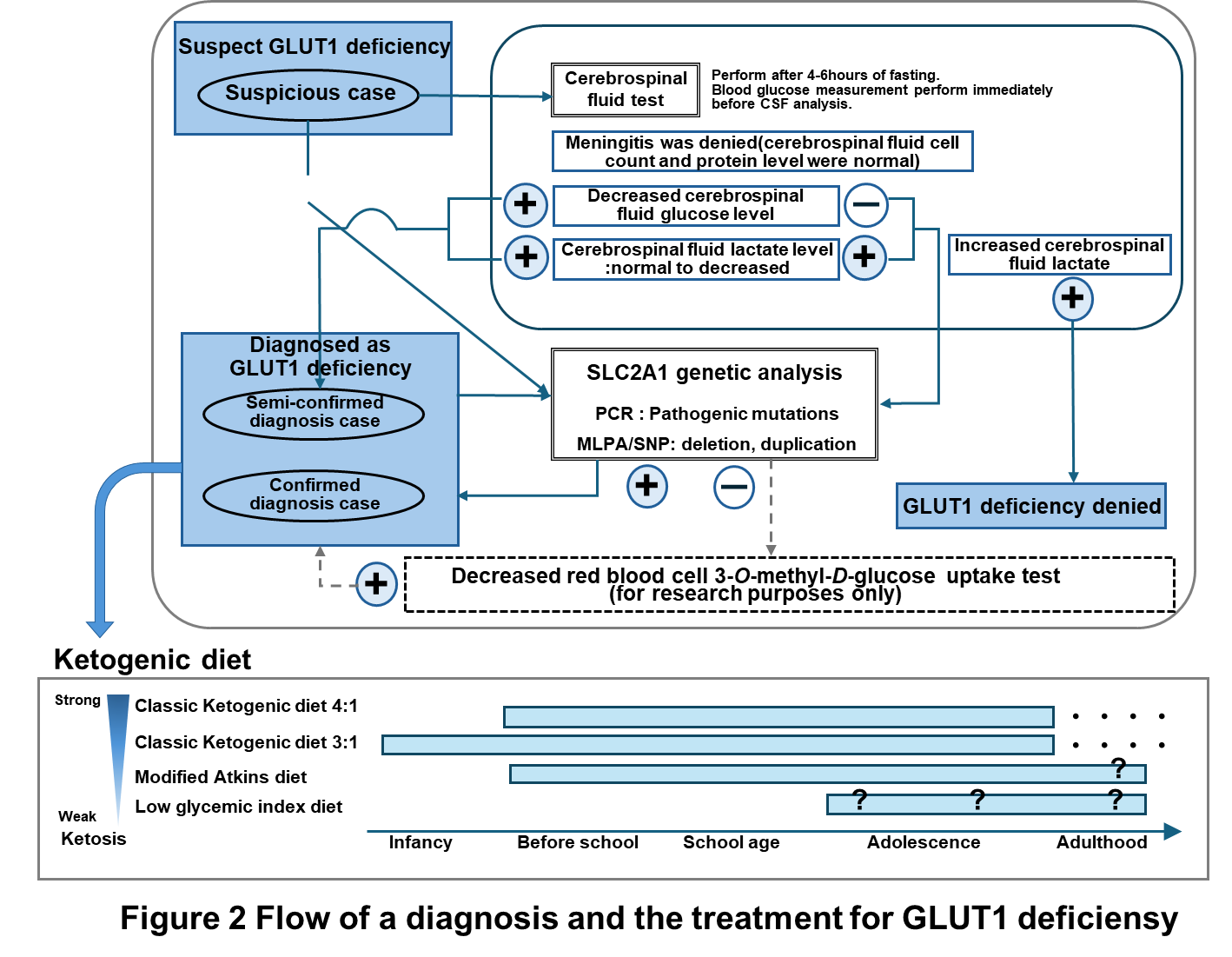

When GLUT1 deficiency syndrome is suspected based on symptoms and characteristic findings, a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) can confirm a low glucose level in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). If low CSF glucose levels are confirmed, the diagnosis is highly likely. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through genetic testing that identifies mutations. A nationwide survey supported by the Japan Pediatric Neurology Society has identified over 80 cases, but it is believed that many undiagnosed pediatric and adult cases still exist.

What are the current treatments for Glucose Transporter 1 Deficiency?

For epilepsy seizures, oral anti-seizure medication is administered according to the type of seizure. Rehabilitation and medical care are provided to improve intellectual and physical abilities that have been reduced by the disease, and to regain basic motor skills and social adaptability.

In addition to symptomatic treatments that aim primarily to alleviate superficial symptoms, there are dietary therapies that are closer to treating the cause of the disease. The ketogenic diet (Figure 1), which is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet that can supply ketone bodies to the brain as an energy source instead of glucose , is clearly effective in suppressing epileptic seizures and other seizure symptoms, and also improves intellectual ability, motor ability, brain alertness (alertness), and motivation, so it is expected to improve the quality of life of patients and should be started upon early diagnosis. There is also preparation dry milk called ketone formula, which makes it possible to treat patients from early infancy. There are several types of ketogenic diets, including the classic ketogenic diet and the modified Atkins diet, but there is no significant difference in their effects (Figure 2). The choice of which to choose will be decided in consultation with your doctor and nutritionist.

Currently, it is considered advisable to continue the ketogenic diet even after adolescence. In mild cases, the decision to continue the diet or to start a new diet in cases diagnosed in adulthood should be made in consultation with the attending physician, considering the benefits and disadvantages. For children with mild symptoms, some families have difficulty getting their children to eat because they do not see any benefit in continuing the diet if the improvement in symptoms is minor. In addition, there are many concerns about continuing the ketogenic diet, such as long-term side effects, restrictions on daily life (going out, staying overnight, going to school, going to a facility, entering a facility), securing and cooking food in the event of a disaster, financial burden, and the lack of a cook other than the mother. The development of safe and effective new treatments is expected to provide patients and their families with additional options. Additionally, the promotion of simple and less burdensome testing methods is anticipated to facilitate early treatment initiation.

Yasushi Ito, Research Department of Pediatric and Maternal Health, Aiiku Research Institute Aiiku Maternal & Child Health Center /

Department of Pediatrics Tokyo Women’s Medical University